The Filibuster Strikes Again: How It Inhibited Workers’ Rights in the 117th Congress

January 3, 2023

By Emily DiVito

In the most recent Congress—the 117th, running from January 3, 2021 to January 3, 2023—Democrats had unified control in the House and Senate and a pro-labor executive in President Biden. Despite this, the filibuster killed several key pieces of legislation that would have directly benefited workers and their families. In recent decades, the routine threat of the filibuster in the United States Senate has effectively created a 60-vote threshold for passage of most pieces of legislation. This has been especially true for legislation that would have helped workers or reined in corporate influence. The 117th Congress was no exception.

In fact, when pro-labor policymakers and advocates were able to secure some wins for workers in this past Congress—like, for example, the prevailing wage and apprenticeship provisions embedded in the Inflation Recovery Act (IRA)—they were largely achieved using filibuster-proof mechanisms like budget reconciliation. Reconciliation only requires a simple majority, but it also dictates the structure of the programs included and is biased toward indirect policies like tax credits. As the 118th Congress—which will last through 2024—begins, the filibuster’s continued stranglehold looms large. The only way to deliver sufficient and timely relief to the American people—especially workers and their families—is to abolish it.

The filibuster, erroneously considered a foundational feature of the Senate, was not part of the founders’ original vision: It was an accident.

The filibuster, erroneously considered a foundational feature of the Senate, was not part of the founders’ original vision: It was an accident. When the Senate tried to simplify its rulebook in 1806, it eliminated a provision that had required only a simple majority to end debate on a bill and move to a vote. In the absence of this procedural motion, a loophole was formed whereby Senators could hold the floor—and so refuse to end debate on a bill to delay a vote—indefinitely. For much of the Senate’s history, filibustering was rare and norms prevented abuse. But, in 1917, after several senators blocked a military arms bill, the Senate created the Cloture Rule to formally end debate and force a vote. Today, a motion to invoke cloture—and so force a vote—must meet a 60-vote threshold. The ultimate passage of the bill is subject only to a simple majority vote.

There is no precise record of how many filibusters have been initiated, in part because whether or not one is being conducted is sometimes unclear. Failed cloture votes are the best available proxy—but not all filibusters trigger cloture votes, and not all cloture votes follow filibusters.

Moreover, the very threat of a potential filibuster has the same effect as an official one: Knowing that a group of Senators could (and probably will) filibuster any given bill effectively imposes a 60-vote threshold on every bill. This threat alone can jeopardize a bill’s viability early in its life cycle and reduce the likelihood that it ever even receives a chance at passage. If with a 60-vote threshold, a bill might not pass—or will for sure fail—then why hold a vote on it?

The filibuster obstructs policymaking of all kinds, but does not do so equally. Its history as a key tool for racially motivated obstruction of civil and voting rights legislation is documented relatively well. But it’s also been leveraged to hinder progressive economic policymaking—historically with great success.

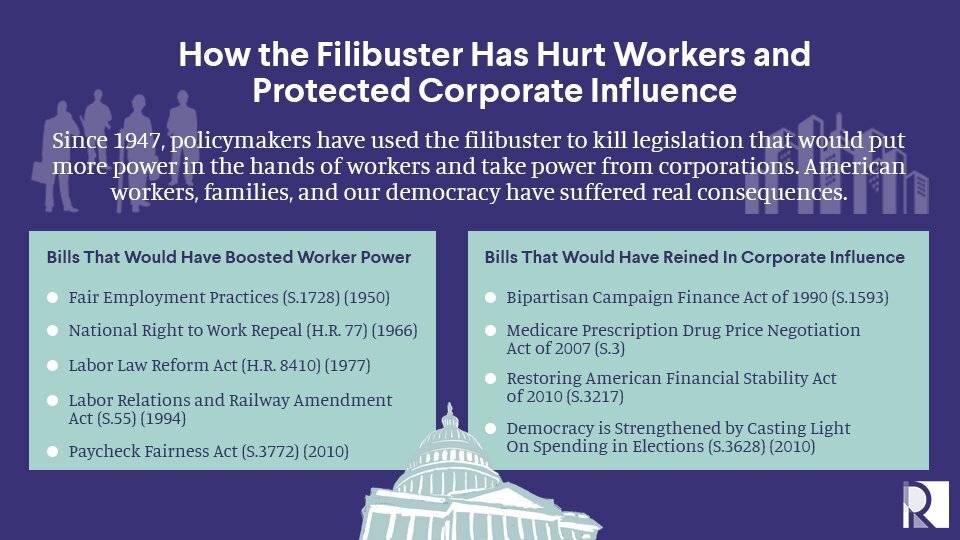

In previous research, I’ve found that, since 19471 and 2020, eight pieces of legislation that would have benefited workers or reined in corporate influence were passed by the House, received more than 50 votes in the Senate, had the support of the President at the time, but failed to overcome a filibuster.

In the 117th Congress, the filibuster was similarly deployed to kill legislation that would have benefited workers and their families. The following bills passed the House with bipartisan votes and had the support of President Biden. Though not all had formal proof of a filibuster in the form of a failed cloture vote in the Senate, all at least had documented threat of one.

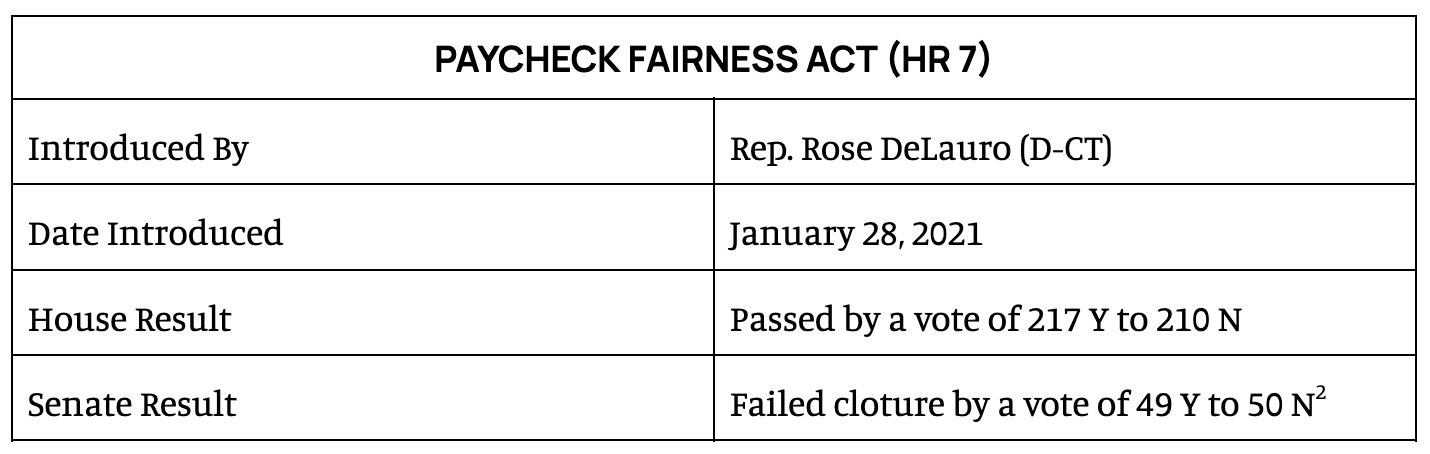

Like its predecessor, the 2021 iteration of the Paycheck Fairness Act would have made it easier for women workers to raise pay discrimination claims against their employers. It would also have authorized and funded the Department of Labor to educate the public about pay discrimination and provide negotiation training programs to help create equitable workplaces. It passed the House and had strong support from President Biden, but narrowly failed a cloture vote in the Senate.

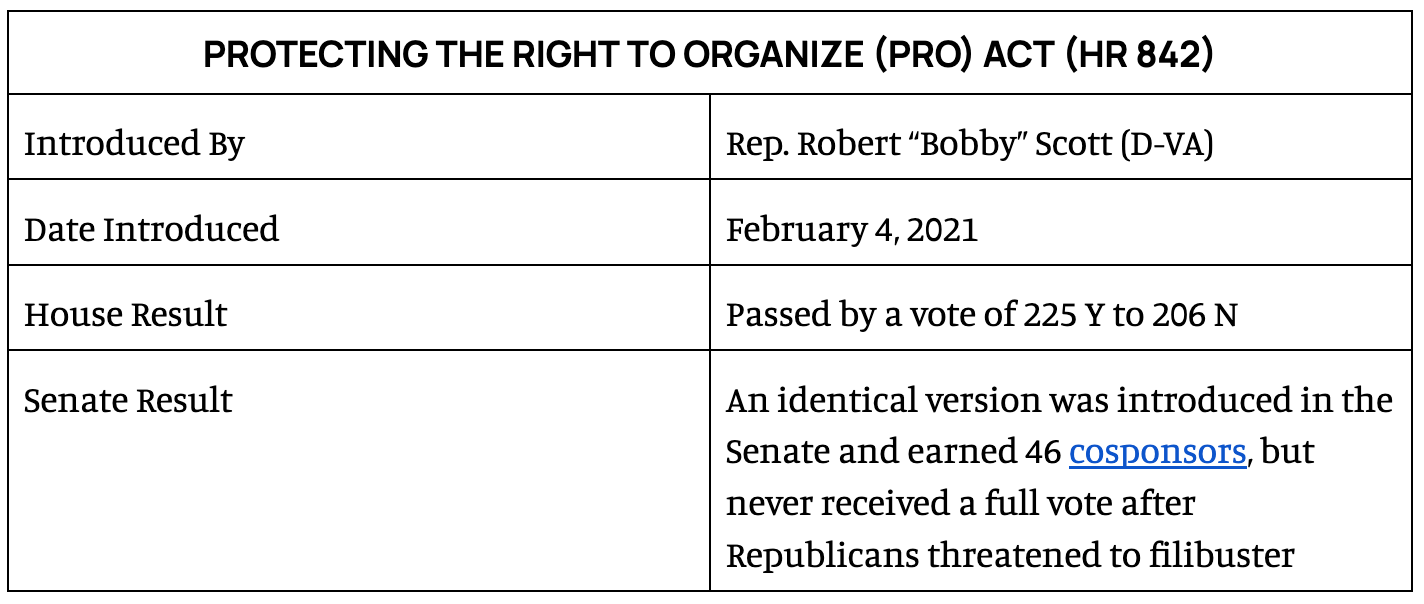

The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act would have delivered the most significant and comprehensive pro-worker labor reforms in decades. Strongly supported by workers and their unions alike, it would have protected and expanded workers’ rights to organize and collectively bargain, and instituted meaningful penalties for companies and executives that violate those rights.

The PRO Act passed the House and was endorsed by President Biden, but failed to earn a Senate vote after Republicans threatened to filibuster.

The filibuster also left its mark in the 117th Congress on bills that did manage to become law.

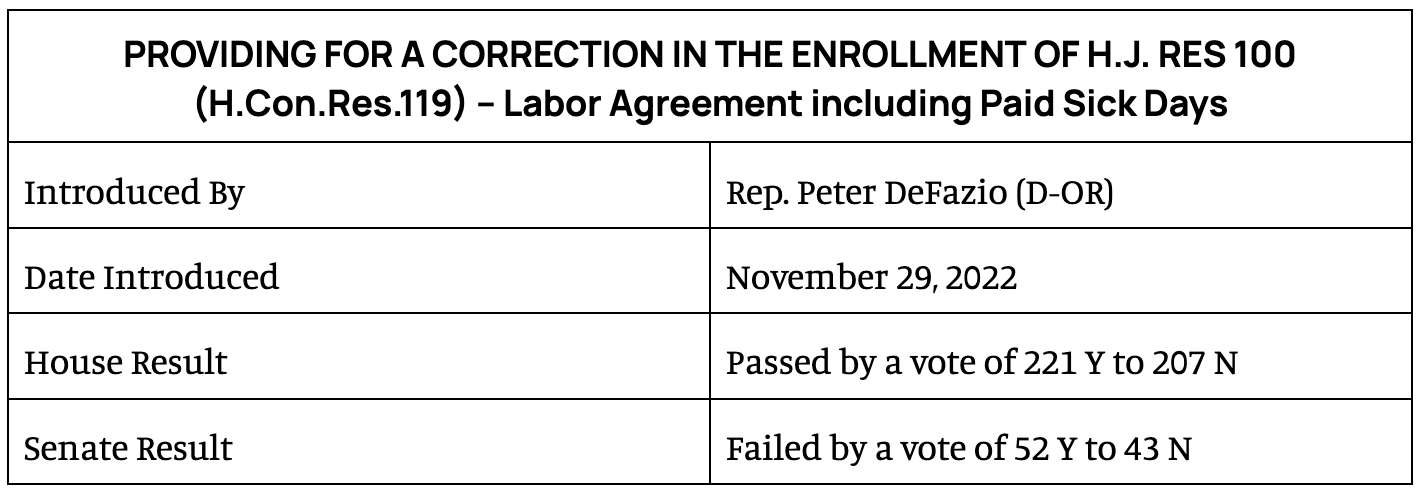

When some of the largest unions of the nation’s freight rail industry—the backbone of the US supply chain, and covering tens of thousands of workers—rejected a five-year contract brokered earlier in the fall of 2022, President Biden intervened by asking Congress to vote on a labor agreement to prevent a rail shutdown. The (entirely justifiable) sticking point for the workers was paid sick days, of which they’re guaranteed none. The worker-preferred labor agreement, which included seven paid sick days and had passed the House, failed to secure enough votes to override a Senate filibuster. In its stead, a similar resolution, but without any paid sick days (and so without the threat of a filibuster), passed both chambers and was signed into law, preventing a strike but once again highlighting the strength of the filibuster’s grip on policymaking.

In addition to all of the pro-labor bills described above that languished due to the filibuster in the 117th Congress, many more pro-democracy and civil rights bills were similarly felled. Perhaps most notable of these were the For the People Act—which would have expanded voter registration and voting access, restricted disenfranchisement efforts, and required states to establish independent redistricting commissions—and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act—which would have reinstated Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to require states with a history of voting discrimination to “pre-clear” any changes to voting rules with the federal government. Both passed the House and had the enthusiastic endorsement of President Biden, but stalled out after Republican Senators threatened to filibuster.

When workers and their unions benefit, everyone benefits. Unions help provide higher wages and better health and retirement benefits, and reduce racial resentment and inequality—for their members and non-members alike.

That’s precisely why the filibuster must be eliminated. Despite the filibuster’s chokehold, pro-labor President Biden and a unified Congress were able to secure many worker initiatives. Without it, they could have accomplished even more for workers and their families. As the 118th Congress begins, may its members heed the lessons of failures past, and abolish the filibuster.